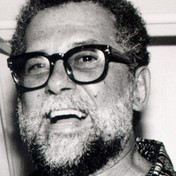

Ilumencarnados seres

capinan

Interviews

Ana de Oliveira – Capinan, please talk about your political militancy in the 60’s.

Capinan – When I started my undergraduate studies at the School of Law, I enrolled in the Communist Party. Until around the 70’s I still felt connected to the Party. At Centro Popular de Cultura (CPC – Popular Center of Culture), I worked as an actor and as an author. It was then that I wrote my first play, songs composed by Tom Zé, who was also at CPC. From this militancy period on, I could no longer detach culture from politics. To me, poetry’s role was to reveal the structures of the world. But even at CPC I never thought that politics prevailed over aesthetics.

Ana de Oliveira – Was there an opposition between the avant-garde and the Left?

Capinan – In the cultural magazines of that time, for instance, there wasn’t such opposition. The avant-garde was connected to the Left. The debate on Concrete Poetry was open. Engaged art didn’t mean art with no aesthetic concern.

Ana de Oliveira – Which were the main influences in your formation?

Capinan – I was born in the rural zone, in a house without books. I educated myself in the streets of Salvador, managing to surpass the archaic structure of my family, listening to oral literature and watching popular movies. I needed art as a way of freedom, including a political freedom. I immersed myself deeper in modern poetry when I was at the CPC. The militancy opened my horizons. Besides Greek tragedy, I started to read Brecht and his way to perceive the relation between actor and audience fascinated me.

Ana de Oliveira – You were integrated into the Tropicalista project primarily as a popular song lyricist. But how was your political and philosophical participation?

Capinan – When I say that in Tropicália there was not a very programmed thing, I don’t mean to say that there was not an intention net, but simply that it was very different from CPC, for example. Gil and I had already felt that the generation coming out needed an intensified element for its sense of urge but didn’t know how to give shape to it. We gathered to search for what was missing, for what would replace in a certain way the CPC and the Opinião.

Ana de Oliveira – Together with Torquato Neto, you wrote a TV program entitled “Vida, Paixão e Banana do Tropicalismo” (Tropicalismo: Life, Passion and Banana). What was the format of this program? What did it aim at? Why didn’t it go on the air?

Capinan – Until today I think that only a revolutionary Tropicalista delirium could conceive a program like that. It was a delirious panorama. The question of guerrillas was clearly in it along with a quotation by Che Guevara, who had just died. Exterminating the guerrillas was a continental priority. Even being a communist, I wasn’t in favor of it but admired Che’s romantic purity. The program was a rebellious idea that wouldn’t leave anything in its original place.

Ana de Oliveira – The song Soy loco por ti América, whose lyric is yours, seems to have fulfilled, in the aesthetic plan, the purpose of integrating all Latin America. Was it your intention with a lyric that intermingles Portuguese and Spanish?

Capinan – My intention was to register the emotion derived from Che Guevara’s death. I didn’t want to say that I was Latin-American, although I felt that way. I had been connected to Cuba since Fidel Castro’s revolution. In the lyric, I looked for words in Portuguese and Spanish that didn’t sound like they came from different languages. Furthermore, there was that thing of the aesthetics from the continent in a time in which many issues of different countries were closely related.

Ana de Oliveira – Tropicália’s manifesto-album presents, at the beginning and at the end, songs with essentially catholic references: “Miserere Nobis,” by you and Gil, and “Hino ao Senhor do Bonfim.” What is the reason for the Tropicália themes to be focused on Christian devotional religiosity?

Capinan – This is a fundamental question, because I had never realized how much I was in tune with the Christian values of my formation. Anytime I start having any critical, political or aesthetic awareness, I’m always questioning the Holy Trinity, the existence of Hell, sin, guilt. It is with the university that militancy comes, and religion is my counterpoint.

Ana de Oliveira – Please, explain the following metaphor by yours, a kind of paraphrase of Vinicius de Moraes: “O Tropicalismo quis e conseguiu ser uma chuva de verão que alagasse infinita enquanto durasse.” (Tropicalismo wanted and got to be a pouring summer rain that would flood infinitely while it lasted)

Capinan – From the beginning, I thought that Tropicalismo shouldn’t be neither aesthetics nor tradition. In this sentence I point out the Tropicalista virtue of being something that had its turn, that fulfilled its role very well and stepped aside. It was the piece that was missing in that time’s puzzle.