Ruídos pulsativos

geleia geral

Tropicalism occurred at a key moment in Brazil’s cultural history. Alongside the musical renewal instigated by the Bahians and their companions, other areas were also undergoing exciting changes. The “geléia geral” (“general jam”), an expression coined by the poet Décio Pignatari that became the title of the manifesto-song of Torquato Neto and Gilberto Gil, referred to a country whose society was divided and contradictory, on the threshold of modernity (Formica, television, the Jornal do Brasil newspaper), yet still hooked on tradition (bumba-meu-boi – a folkloric dance from Maranhão state, mangos, an indigo sky). Cinema Novo, (the Brazilian New Cinema), the theater and its groups of players such as Arena and Oficina, deep critical thought in newspapers and magazines and a series of revolutionary works in the visual arts created the conditions for the movement’s esthetical radicalism.

Works linked to Tropicalism assumed a critical position in the participation of Brazilian art in the international urban language. To be a Tropicalist was to think about and propose a new image for Brazil. By appropriating the transgressive elements of world art, of mass culture and of pop music, the aim of its participants was to universalize not only popular music, but all Brazilian culture.

The movement brought the controversial introduction of the electric guitar and bass to the arrangements of its songs, breaking with the traditional acoustic format of Brazilian popular music. Its international influences ranged from the Beatles and their experimental album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band to Jimi Hendrix’s guitar and the singing of Janis Joplin. Also highly relevant were two extremes: the participation of erudite maestros from the group Música Nova, above all the genius of Rogério Duprat, and the pop movement of the Jovem Guarda (Young Generation).

“Um poeta desfolha a bandeira e a manhã tropical se inicia resplandente, cadente, fogueira num calor girassol com alegria na geléia geral brasileira que o jornal do brasil anuncia.”Gilberto Gil e Torquato Neto

In the domestic context, Tropicalism benefited from contacts with other artistic areas that had been in the vanguard ever since the fifties. Works with the most obvious connections are the movie Terra em Transe (Enchanted earth), by Glauber Rocha, and the play O Rei da Vela (The Candle King), produced by José Celso Martinez Corrêa. Both film and play were seen by Caetano Veloso and incorporated into his repertoire of references. Others, just as important as these two, although less talked about, were the art installation Tropicália, by Hélio Oiticica, and the book Panamérica, by writer and filmmaker José Agripino de Paula. While the first gave its name to the movement and brought an anthropophagic proposition to the conception of its works, the second launched a poetry in which the use of the elements of American pop culture was innovative and instigating.

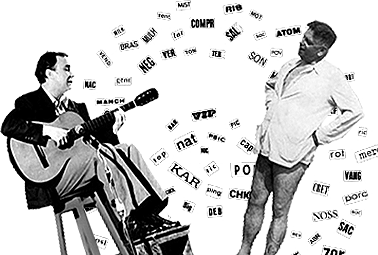

In the songwriters’ circle, some people, such as the designer and philosopher Rogério Duarte, had a fundamental influence on the Tropicalist propositions, with their ideas and sometime participation. The same happened in the field of criticism, with the Concrete Poetry of the Campos brothers and of Décio Pignatari. It was the Concretists who backed the movement right from the beginning. Through them, the songwriters discovered the anthropophagic poetry and philosophy of modernist Oswald de Andrade, author of the Manifesto Antropófago (Anthropophagic Manifesto) and the play O Rei da Vela (The Candle King).

All this “general jam” was acclaimed by the Tropicalists as favoring freedom and risk. Their actions were, in the words of Décio Pignatari, the “flesh and bone” of Brazil’s cultural renewal.