Ruídos pulsativos

Marginália

Far from being merely a revolution in 1960s Brazilian Popular Music (MPB), Tropicalism was a broad cultural revolution. Musicians did not just experiment with the music itself, but adopted a strong visual image in order to present themselves and their ideas to the public. Influenced by reading Marshall McLuhan, with his dictums that ‘the medium is the message’ and clothes being ‘an extension of the body’, a performer’s visual image began to be just as important as the ideas contained in the lyrics of the songs or in declarations to the public.

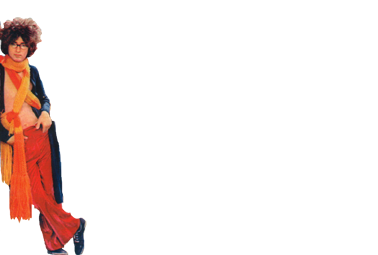

Thus, record covers, stage sets for concerts and, above all, the clothes used on stage and for other public appearances were a source of shock and scandal to the public at large. At the same time, they were fundamental elements in the popular success of the movement and in the permanence of its image. Caetano Veloso’s plastic and vinyl clothes, Gilberto Gil’s colorful Indian tunics, the costumes used by the Mutantes and Gal Costa’s aggressive hair-styles and overall image, were all strategic milestones in the creation of the Tropicalist look.

The person behind the majority of these clothes was Regina Helena Boni, a designer from Minas Gerais. Her shop Ao Dromedário Elegante (At the Elegant Dromedary) which opened in 1968 in São Paulo’s smart Rua Bela Cintra, became the reference point for the alternative look of the period. It was not just the Tropicalists who wore her clothes on stage, but also the ‘Jovem Guarda’ (‘young generation’) stars such as Roberto and Erasmo Carlos and Wanderléa. Another of her ‘models’ at this time was the TV presenter, Chacrinha, a key character in Tropicalism. Interviewed in connection with Tropicalist fashion and her creations, the designer claimed that her inspiration for the clothes came from her dialogue with the words of the songs and the ideas that the musicians were transmitting. Her designs not only dressed the singers but were a key part of the performance’s overall visual concept.

In the following decade, fashion was to unpeel itself a bit from the musical movements and invade counterculture territory, incorporating once and for all the hippie look as alternative dressing for the young. The radicalism of marginália began to substitute the bananas and bright colors of Tropicalism. In 1968 and 1970 respectively, the reporter and photographer Marisa Alvarez Lima wrote two articles about the new trends in the magazines A Cigarra (The Cicada) and O Cruzeiro. Her headings – “Anti-fashion – mutant fashion” and “Anti-fashion – ‘marginal’ reaction” – make it totally clear that an alternative visual movement was in course in Brazil. In these articles, she put forward the concept of ‘anti-fashion’, or ‘marginal’ fashion, present in the clothes of Regina Boni’s Dromedário Elegante and the Rio boutique Frágil, owned by Célia Azevedo and the painter Adriano de Aquino.

Located in Ipanema, near the beach and the famous “dunas do barato” (‘getting-high dunes’) Frágil continued on the route of experimentation started by Regina Boni and her shop in São Paulo. In an article about the Rio boutique, the fashion rationale behind Frágil is written about as if it were a type of manifesto defining the idea of anti-fashion, with its “subterranean reaction in the quest for total liberty”. According to this manifesto, fashion had turned into “a magic act that renews itself” and “a pacific process against the establishment”. The bottom line was – this was a time when dressing, even out of shops in fashionable Bela Cintra and Ipanema, could also be a ‘marginal’ attitude.